Müpa Film Club

Music Till Death Do Us Part

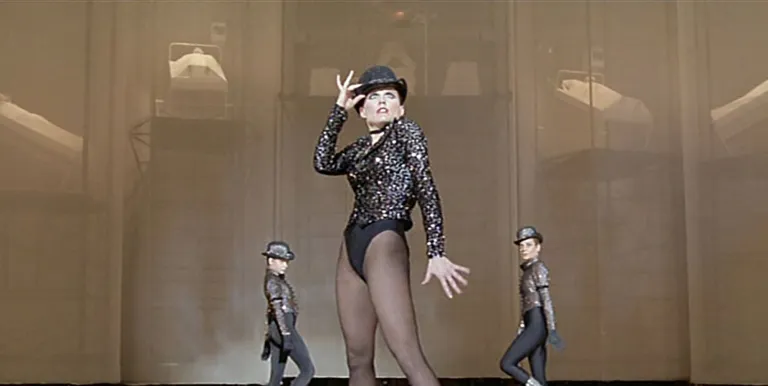

“What am I without music?” sang Péter Máté, and it is a sentiment we can fully identify with. The new season of the Müpa Film Club has the kind of music as its focus that inspired the inception of a number of films of era-defining significance. Once again, our audience has a wonderful selection to pick from in 2026. As part of the screenings, Lars von Trier’s powerfully elemental melodrama Dancer in the Dark, which achieved huge success starring Björk, will be joined by György Szomjas's 1981 cult film Kopaszkutya (Bald Dog) on the Auditorium’s big screen. The authentic American vibe is brought to life by, among other offerings, Ralph Bakshi’s animated feature American Pop and Robert Altman's Nashville, but, of course, the outrageous parody of The Rocky Horror Picture Show could not be ignored, and the same goes for All That Jazz. The icing on the cake is the bewilderingly diverse and captivating Moulin Rouge!, where the performances of Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor ensure there won’t be a dry eye in the house.

Before and after the screenings, the film critic András Réz’s open-ended conversations, full of fascinating details and behind-the-scenes secrets, will help viewers immerse themselves even more deeply into the films.

Come and join us!

We kindly draw our guests’ attention to the fact that the usual screening time of the Müpa Film Club has changed, so please pay attention to the new start times.